A weaker media ecosystem’: Why publishers are pessimistic about the next round of News Media Bargaining Code talks

Welcome to Tuesdata, our weekly analysis for Unmade’s paying members.

Below, we examine how consequential the next round of News Media Bargaining Code negotiations could be for the Australian media landscape.

Further down, a down day for Seven on the Unmade Index.

The content of the full post is available only to Unmade’s paying members. That could be you. Not only can you see today’s members-only edition of Tuesdata, but you get access to the full Unmade archive, which goes behind a paywall two months after publishing. Unmade’s paying members also get discounts on tickets for our events, including next week’s REmade – Retail Media Unmade conference. The coupon code is at the bottom of this post.

How will publishers fare if the Meta money stops?

Seja Al Zaidi writes:

In 2021, Australian political parties rallied behind a law that pushed Google and Facebook to help pay for the news they distributed on their platforms.

The threat of the News Media Bargaining Code nudged Google and Facebook to sign deals with publishers. Under the law, once a digital platform was designated by the government, it would be forced into binding negotiations with publishers. The passage of the law was enough to bring Facebook and Google to the table to ward off designation.

The result was more than $200 million injected into the revenues of Australia’s largest publishers, along with some of the smaller ones.

Although deals were confidential, most Facebook deals seem to have been for three years, while Google’s may run slightly longer. That first tranche of money will stop at the end of this financial year. While most in the market appear to anticipate a new set of deals from Google, they are more pessimistic about Facebook and its parent company Meta doing the same. They say that Meta is more antagonistic to deal with.

Hear more about how the News Media Bargaining Code happened:

One of the signals has come from overseas where Meta blocked news on Facebook and Instagram in Canada rather than be covered by the Online News Act.

Though every publisher deal was struck on a case-by-case basis, the next 12 months will see some of them begin to expire. Publishers and news organisations will be hoping to begin negotiations for a new round sooner rather than later. As a consequence, the commercial fortunes of Australian media will largely be determined in the coming months.

The general consensus amongst publishers is that Meta’s cooperation is unlikely in 2024. And smaller publishers believe that the structure of the law may leave them frozen out while media behemoths with political clout will likely fare better.

Below, we speak to some of the most influential publishers in Australian media including Nine’s managing director of publishing, James Chessell; Private Media CEO Will Hayward; Digital Publishers Alliance founder Tim Duggan; Broadsheet founder Nick Shelton; and co-founder of Man of Many, Scott Purcell.

“I have always held the view that the Media Bargaining Code is fatally flawed. I am not surprised that many people think that one of the two designated platforms is unlikely to be funding media,” says Will Hayward, CEO of Private Media, which owns Crikey, Inc., SmartCompany and The Mandarin.

“It’s hard to diagnose the specifics of something that is so catastrophically flawed as the Bargaining Code. The Code was always flawed. It’s flawed from its basic starting point, which is that two foreign owned technology companies should decide which media companies receive how much additional funding.”

“A fair conclusion from there is that some sort of intervention is required in order to improve it with a specific focus on pluralism and less concentration of ownership. To go from that to then think Google and Facebook should be the ones who decide where that investment goes – it’s just ridiculous,” Hayward adds, noting that the issue of concentrated media ownership in Australia leaves independent publishers in a state of greater need for supplemental funding, preferably from government.

It’s a view shared by Broadsheet founder Nick Shelton, who says “the intention behind the policy was terrific. I think having $200 million into the media ecosystem is, on the whole, a good outcome. But the idea that it was left up to Google and Facebook to decide who they were and weren’t going to negotiate with just meant that it wasn’t completed. They got 90 percent of the way there and fell over at the finish line.”

Broadsheet were not recipients of any funding. Shelton’s story was commensurate with many other small publishers, who were taken far less seriously by Meta and Google and offered much smaller sums compared to their mainstream counterparts.

“Google told us that because they didn’t have to negotiate with us, they weren’t going to. They offered us a very lowball offer just to kind of deal with us. We knew that wasn’t commensurate with what other publishers had received, so we said no, and frankly, it just wasn’t meaningful for us. So we got left out.”

Former Junkee co-founder Tim Duggan formed the not-for-profit Digital Publishers Alliance after the establishment of the Code. Its members include a bevy of independent publishers like The Brag Media, Mamamia, The Squiz, Schwartz Media, Urban List and more. The DPA receives funding from Google via its US$300 million Google News Initiative and Facebook’s Journalism Project. Facebook has since withdrawn from supporting the organisation.

Duggan expressed that there was clear inequity in how funding was being distributed, and that smaller players – indeed, members of DPA – would be damaged if Meta wound back its funding, which he was clear was likely to occur.

“The News Bargaining Media Code is extremely unbalanced, with the large majority of funds going to already established legacy media companies with healthy bottom-lines. This is due to lobbying, media pressure, government alliances and by design of the legislation,” Duggan says.

“Not receiving funding in future rounds would have a hugely detrimental effect on smaller publishers. It will result in direct job losses, decreased content creation and a shrinking of the industry. There will be a direct impact if Meta does not renegotiate their deals – and so far every indication says that they will not renew their deals,” Duggan adds.

While there’s a clear asymmetry in the priority of funding between large media organisations and smaller, niche independents, the argument can be made that lifestyle publishers don’t necessarily deserve the same funding as organisations that are expending substantial amounts of resources, time and risk on public interest or investigative journalism.

“I’m not particularly worried about lifestyle journalism. The original intention of the Media Bargaining Code was to deliver additional funding to public interest journalism. It’s very explicit. It’s for public interest journalism. There are very few independent, public interest journalism outlets in Australia. And I think those of us out there have got a tough ride ahead of us,” Hayward says.

Shelton had a markedly different perspective.

“I think that what Broadsheet does is in the public interest. We are a culture publication and culture is so meaningful to healthy societies and democracies. Another part is that we exist in the same business. So even if we cover our topics differently, we still hire professional journalists. We still have to deal with the ecosystem created by Facebook and Google. We still have to deal with them as unavoidable trading partners, and so we get squashed. And so what happens is if the playing field is even, if nobody gets funding, then that’s fine – we compete. But if our competitors, including News, Nine and Guardian get funding, and we don’t, we get crushed,” he says.

The Sydney Morning Herald, The Age and the Australian Financial Review produced some of the most consequential moments in public interest journalism this year. Nine’s managing director of publishing, James Chessell, says disengagement from the tech giants could spell struggle for newsrooms trying to sustain that type of reporting.

“It would undoubtedly have a detrimental impact on those remaining newsrooms that are doubling down on public interest journalism, because public interest journalism is the most expensive and the most risky journalism you can do,” Chessell says.

“The contributions from the digital platforms has made it easier for us to invest in our newsrooms and public interest journalism in a responsible and sustainable way.”

The role of Canberra clout

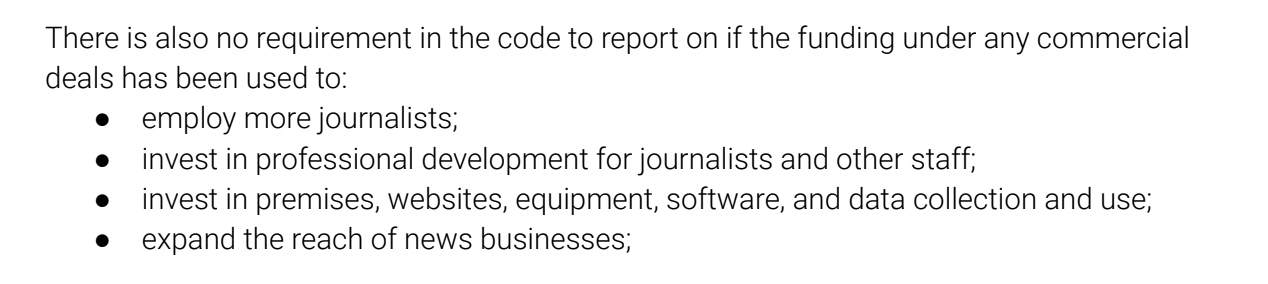

One of the key issues created by the architecture of the Code is that media giants with more resources and lobbying power are using it as a means to boost their bottom lines. There is no obligation for the extra funding they receive to go directly into journalism jobs.

The deals are also confidential, so publishers do not reveal how much each of them get. According to Nine’s latest set of ASX numbers, its publishing division make a total profit of $164m on revenues of $575m. The Google and Facebook money likely sits within a $180m pot labelled as “subscription and licensing” digital revenue.

“The issue that we have is that two media companies own the vast majority of print media and all media in Australia. The issue is that we need more funding into independent outlets in order to reduce the concentration of ownership. That’s the issue. It’s not that News Corp isn’t profitable enough,” says Hayward.

“The Code operates under the threat of designation as a key driver for platforms offering deals, so the platforms have only to satisfy the loudest voices in the room in order to quell the threat, leaving many smaller and independent publishers without any funding,” added Duggan.

Larger publications receiving more funding then enabled them to more easily poach journalists from publications that been unsuccessful in securing anything from Meta or Google.

“The cost of hiring a journalist has gone up by over 20% the last few years”, says Broadsheet’s Shelton. “It’s been very competitive, so all the publishers we’re talking about who’ve been funded, they come for our best journalists, and they throw money at them, and it just means that we have to increase our rates, but we don’t have the revenue to support it like they do.”

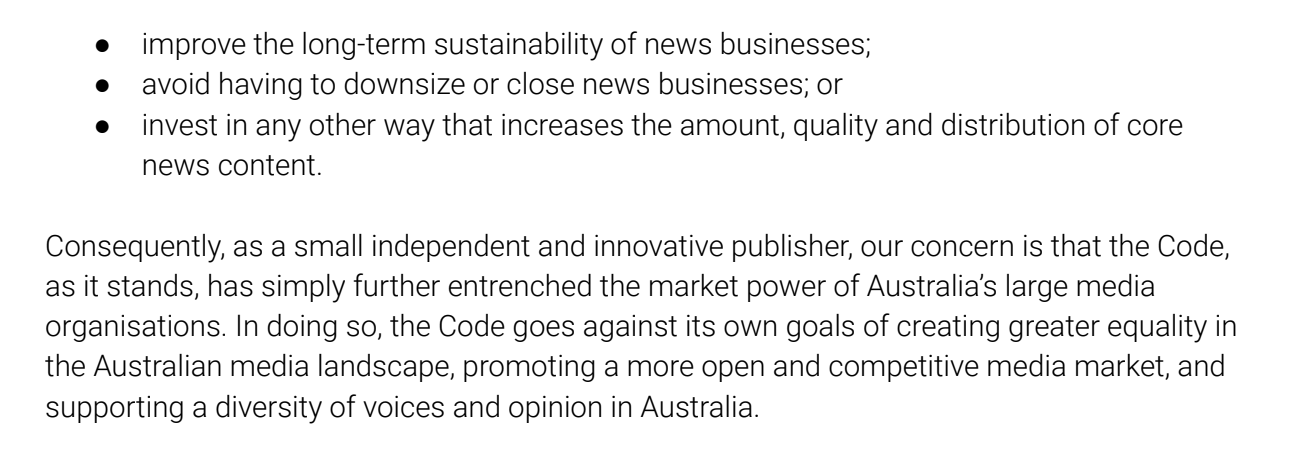

Scott Purcell, co-founder of men’s lifestyle site Man of Many, describes it as a “huge problem” that outlets receiving funding aren’t detailing how they’re spending the funding, or exactly where they’re directing it in organisations.

In the publication’s submission to Treasury, he outlines that large news organisations, who have been granted funding much more easily, have had their market power further ‘entrenched’ by not needing to report where their funding is being directed. Nine’s Chessell says the funding was ‘spread across all parts of the newsrooms’ including traditional reporting roles, distribution roles and editing roles.

Purcell adds that political prowess and relationships long held by the legacy publishers have been what’s bolstering their ability to be prioritised for funding.

“Reading between the lines, it’s very much likely political pressure. The larger legacy publishers have a lot of say in Canberra, so they have the ability to fund lobbyists, they definitely have the ear of the government. Both parties supported the News Media Bargaining Code because they want to keep the large media companies onside.”

Shelton questioned whether that political power would sustain the legacy media when it comes to the next round of negotiations.

“I think that it’ll be interesting to see when News and Nine and the other very influential publishers take this up with government, how the government will respond and whether they’ll take this seriously or they just sort of let it go.”

A consequential 2024

The elephant in the room is that less funding may mean broad redundancies in newsrooms across the country.

The provision of an estimated $200 million in funding from Meta and Google has been helping keep some media organisations afloat in the last two years, particularly in a weakening advertising environment and a digital subscription market which is yet to reach maturity.

“The logic for the deals that existed in the first place still exist. The market power of the big tech platforms has not diminished, in fact it’s strengthened. Therefore, the arguments that they should in some way compensate publishers that are in the business of public interest journalism remains,” says Chessell.

“We have some concerns about the arguments Meta has made in its submissions to the Treasury process here and about what’s happened in Canada, and its positioning in other jurisdictions, but we look forward to engaging with them constructively.”

Back in August, Nine CEO Mike Sneesby argued during reporting season that the increasing use of Nine’s video content on platforms like Meta’s Instagram and Facebook Reels would strengthen the company’s argument for another deal.

Though the tech platforms’ market power has augmented since the initiation of the code, other publishers were still firm that they weren’t best placed to be the gatekeepers of funding for journalism.

“If you’re of the view that media ownership is overly concentrated in Australia, you might also decide that it needs additional funding from other sources, says Private Media’s Hayward. “The most reasonable place for that to come from would just be from the government directly. And they could do that either with direct or indirect means, so they could do it through additional tax breaks, or they could do it through grants. I think it’s really important it’s not left to the whims of any particular governing party at any given point in time.”

In July, Unmade spoke to Scire founder Chris Janz, who led negotiations with Google and Facebook during his time at Nine, and then helped NZ publishers do the same.

During that interview Janz warned: “The Meta renewals are up within the next 12-ish months. There’s a real challenge ahead for people who’ve built parts of their business off the back of that revenue. When you have what might be $100m a year disappearing from the funding models through Meta withdrawing from the country… I think it is going to pose a challenge.”

“The media ecosystem now has 200 million dollars in funding from that revenue source that’s about to dry up,” says Shelton. “That’s going to have huge implications on the workforce, on salaries, on the cost base of these businesses, and the revenue as well. I think it’s going to throw a real spanner in the works. I don’t see any reason why Google or Facebook would feel like they have to negotiate with us if the government didn’t stand up for us last time. This new government have shown even less interest in the issue.

“I think the consequences are that a lot of journalists and other people in the media ecosystem will lose their jobs. I think it’ll mean a weaker media ecosystem. I think it’ll mean a diminished place for media in Australia, which is a real shame.”

Google did not respond to request for comment. Meta declined to comment. News Corp declined to comment.

Unmade Index takes a holiday

Tim Burrowes writes:

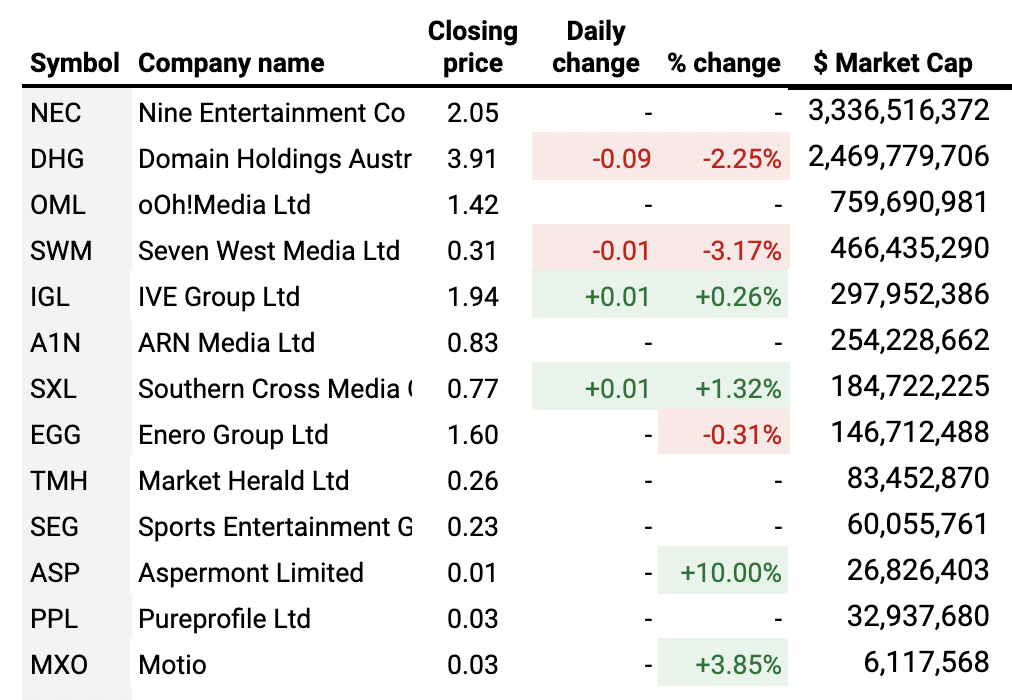

It was a light day of trading for The Unmade Index on Monday, with most of the country enjoying a public holiday. The Index, our tracker of ASX-listed media and marketing companies blipped downwards by 0.65% to 628.2 points.

Of the larger media companies, Seven West Media had the worst of it, losing 3.17%. The SWM share price of 30.5c is only just above its one-year low of 29c.

That’s all for today. Thanks, as ever, supporting us through your membership.

Don’t forget that Unmade’s paying members – including you – get an extra 30% discount on our event tickets – that includes REmade, which takes place in a fortnight. Your coupon code is below.

We’ll be back with more tomorrow.

Your coupon code for RE:Made:

Unmade members get a 30% off tickets for REmade – Retail Media Unmade.

Your coupon code is:

Unmade_Member

Go to remade.net.au and enter the coupon code to access your discounted tickets.